Kananaskis map navigates risk levels of avalanche terrain

April 12, 2024

By Jessica Lee, Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

A new, innovative tool has slid onto the scene to help outdoor enthusiasts make better decisions when planning trips in avalanche terrain in Kananaskis Country, or to steer clear of avalanche hazards altogether.

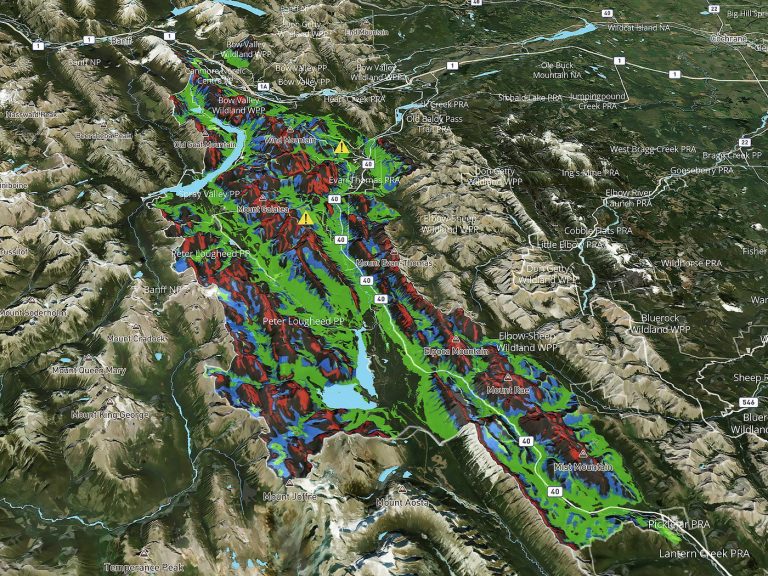

The Automated Avalanche Terrain Exposure Scale map, or AutoATES map, uses geospatial modelling to assess avalanche terrain risk based on factors like slope angle, avalanche runout, terrain traps, start zone density, overlapping avalanche paths and forest density. The result is an interactive, easy-to-use, computer-generated, topographic map that offers valuable insight into avalanche risk levels, ranging from no risk to extreme hazard.

“One of the biggest issues we see for a lot of new people getting into avalanche terrain – and even experienced people – is terrain recognition. The best way to be able to avoid avalanche terrain, if you’re planning on totally avoiding it and going and doing a hike, is being able to recognize terrain,” said Mike Koppang, a mountain rescue specialist with Kananaskis Mountain Rescue.

“This map gives you another tool in your tool bag to help you be able to identify terrain that’s capable of producing avalanches on that five-step model – from no avalanche terrain all the way up to extreme avalanche terrain.”

The map is based on a modified version of the Avalanche Terrain Exposure Scale (ATES), originally developed by Parks Canada staff in the early 2000s. The scale was first developed with three terrain classes: simple, challenging and complex. A second version of the scale was introduced in 2023 by its original developer, Parks Canada Banff field unit rescuer Grant Statham, as well as Cam Campbell of Alpine Solutions Avalanche Services. Version two adds two new classes – non-avalanche and extreme terrains.

The automated mapping project is a meeting of the minds of various avalanche experts and agencies across Canada and internationally.

John Sykes, an avalanche forecaster with the Chugach National Forest Avalanche Centre in Seward, Alaska and PhD candidate with B.C.’s Simon Fraser University avalanche research program, focuses his studies on decision-making in backcountry skiers by looking at GPS tracks and survey responses. He became involved with the AutoATES map initiative through connections with Avalanche Canada.

“Extreme is a little bit of a unique case,” said Sykes of the ATES scale. “It’s one of the newest classes that came out with ATES version two. Essentially, with that, you’re really looking at terrain where even if you triggered a relatively small avalanche, it could still have high consequences because the terrain is so steep that it would cause you to fall and potentially, even if you weren’t buried in an avalanche, you could get injured.”

The strongest driver in classifying extreme terrain is slope angle, and often, little to no forest cover.

“It’s terrain that people are ice climbing in or doing ski mountaineering where usually it’s a big slope, so if you were to get knocked off your feet climbing or skiing, you would have high consequences just from the terrain itself,” he said.

Sykes stressed the map is a complementary product and does not replace avalanche forecasting or other essential trip planning tools.

“It’s independent of the likelihood of any slope avalanching. It’s just looking at, if there was an avalanche there, what would be the consequences,” he said. “From the forecast, you can get information on the characteristics of the hazard right now and then using the ATES map, you could look at where would be some potentially safe places to go today if we have a really dangerous snowpack.

“Then you might want to pick areas that are more in the simple to challenging range.”

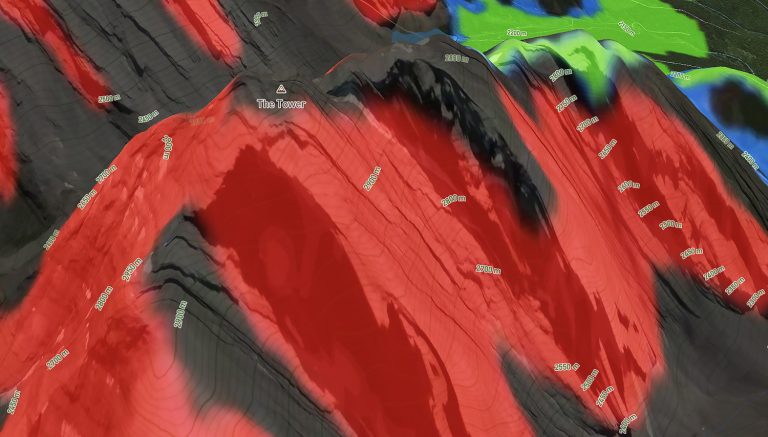

Areas of the map are colour-coded in red for extreme hazard, black for complex, blue for challenging and green for simple. Areas without defined colour have no avalanche terrain risk, according to the scale.

Simple terrain is characterized as having low avalanche exposure or primarily forested geography, with many options to reduce or eliminate exposure to avalanche danger. Challenging terrain is classified as involving exposure to well-defined avalanche paths, start zones or terrain traps like gullies, convexities and slope depressions where options exist to minimize exposure through careful route-finding.

Neither the forecast nor the map replaces having the ability to evaluate such conditions, as well as changing weather while in the field.

“Looking at the terrain, keeping an eye on conditions as they change throughout the day and making your own knowledge-based decisions is still what’s really, really important. That comes a lot from taking a course and learning how to use the terrain starting with an AST 1 (avalanche skills training) course and considering hiring a guide,” said Koppang.

A post shared by Kananaskis Mountain Rescue (@kananaskissafety)

The AutoATES map is intended to serve as an additional tool to aid outdoor recreationists in trip planning and is to be used in conjunction with reviewing current avalanche forecasts, avalanche skills training (AST) and ensuring anyone that enters avalanche terrain – whether to ski, hike, climb or snowmobile – is equipped with proper safety gear, which includes a beacon, probe and shovel.

In light of recent incidents in Kananaskis Country where large skier-triggered avalanches have resulted in fatalities and near misses – events that could potentially have been avoided – the importance of employing resources like the AutoATES map to better grasp avalanche risk grows more apparent.

On March 10, a size 3 avalanche fully buried two skiers who were riding a line down a lower shoulder of The Tower on a northern slope of the mountain in Spray Valley Provincial Park. Avalanche Canada defines a size 3 avalanche as having the ability to bury and destroy a car, destroy a small building or break a few trees.

The north and northeast aspects of The Tower are shown on the AutoATES map as having primarily extreme avalanche ratings, whereas portions of its south and west facing aspects are of lesser risk.

While one of the skiers was able to escape the avalanche, having been buried to the top of his head, the other skier, a 19-year-old man from Kelowna, B.C., was buried much deeper and did not survive the incident, despite the best efforts of his skiing partner to locate and dig him out.

Both skiers were believed to have been swept between 150-250 metres down the mountain, according to Kananaskis Mountain Rescue. The slide was triggered by the skiers and occurred during a special avalanche warning for Banff, Yoho and Kootenay national parks and Kananaskis Country.

A short distance away, on March 24, another skier had a close call in a size 3 avalanche on a northwest aspect of Tent Ridge on a feature known as Tent Bowl. The avalanche was triggered by the skier on their fourth turn down the mountain at around 2,400 metres elevation. Photos of the aftermath show the huge, deep persistent slab avalanche slid far and wide down the slope, burying the skier up to their neck.

“Not only were they lucky to only be partially buried, but they did travel a significant distance down the slope through some sparse forest and they could have easily struck a tree and had a different outcome,” said Jeremy Mackenzie, a mountain rescue specialist with Kananaskis Mountain Rescue in an earlier interview with the Outlook.

Avalanche Canada’s forecast in Kananaskis had the avalanche risk rated as moderate at alpine and treeline at the time, meaning natural avalanches were unlikely but human-triggered slides were possible.

Despite the risk being moderate and on the lower scale of the public avalanche danger scale, which ranges from low to extreme, forecasters in the Canadian Rockies have been calling this forecasting season challenging and difficult to predict with freezing levels. Of particular concern is a persistent weak snowpack layer formed in early February.

The special avalanche warning issued Feb. 29 was in part due to forecasters worried about new snow loading onto the weak layer, combined with warmer temperatures, making avalanches easier to trigger. Most recent forecasts in Banff, Yoho and Kootenay national parks and Kananaskis are calling for conservative choices when recreating in avalanche terrain or avoiding it altogether.

Sykes said the field of digital mapping is becoming increasingly popular as a tool to use alongside reviewing avalanche forecasts, making it more critical than ever to understand the uses for each.

He stressed, again, how much collaboration has gone into developing the AutoATES map.

The initial model for AutoATES was written by Håvard Toft, an avalanche forecaster with the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate, while he was an undergraduate student at the University of Montana. Toft recently co-authored a paperwith Sykes, Statham and avalanche scientist Pascal Haegeli that was published March 20 in the journal of Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences with the results of testing the AutoATES algorithm against manual mapping.

Manual ATES maps were created by avalanche experts and then used as benchmarks and measured for accuracy against automated maps. One of the two study areas was for Bow Summit, a popular backcountry recreation area in Banff National Park. The other was for the Connaught Creek area in Glacier National Park in B.C.

The paper found the overall accuracy of AutoATES compared to ATES benchmark maps for the Bow Summit area was 84.4 per cent compared to manual maps at 84.8 per cent, with variable accuracy across terrain classes. The terrain with the highest rated accuracy for the AutoATES map was simple terrain at 96.6 per cent. The lowest accuracy was for challenging terrain at 59.9 per cent.

“In the Bow Summit study area, the individual manual ATES maps also consistently had the lowest accuracy in challenging terrain, indicating that it is difficult to consistently classify for human ATES mappers as well,” states the study.

“Extreme terrain is another area where AutoATES has high rates of underpredicted pixels and could be substantially improved. Currently, slope angle and forest extent are the only parameters used to delineate extreme terrain. One critical element that is not currently captured in AutoATES is terrain exposure.”

The study further noted the “consequences of falling or being pushed off a steep slope by a small avalanche are critical considerations for extreme terrain” not captured by models used.

It recommended AutoATES maps be used as a first draft to be manually revised by local experts.

“Despite the recommendation of vetting the output of AutoATES maps with local experts before release to the public, the automated system still provides massive improvements in efficiency compared to traditional manual mapping methods,” the study noted.

“AutoATES has demonstrated the ability to classify terrain with similar accuracy to human experts, which presents an opportunity to redefine how ATES ratings are generated and applied.”

The automated map of Kananaskis Country includes only the forecasting area covered by Kananaskis Mountain Rescue forecasters and published on Avalanche Canada.

Currently, maps are only accessible for high-traffic regions where resources can be allocated to minimize time and costs associated with manual mapping.

“AutoATES opens up the opportunity to create low-cost avalanche terrain information across large areas of mountainous terrain,” states the study.

Koppang and Sykes agreed there is an opportunity for local experts to ground truth computer-generated maps in the field and some high-use areas in Kananaskis have already been tweaked to improve accuracy. However, there are limitations based on available resources and the sheer size of some mountainous regions.

The AutoATES map of Kananaskis area was created largely due to local experts’ willingness to take on the initiative and availability of funding.

Sykes said there is appetite to find more research funding to develop more maps in regions with avalanche terrain.

“The whole idea behind the model is that it’s fairly efficient compared to other kinds of avalanche modelling and can be run for large regions, so the ideal application would be to run it for all avalanche forecast regions, but we’re kind of in the process right now of figuring out how we would do that.”

The map for Kananaskis includes a survey, which aims to use feedback to tweak and make improvements.

“Because it is so new, we want to see how we can make this better,” said Koppang. “Like, are there issues with how it’s colour-coded and how could we make it better; do we need the granularity of the map to be better – being able to zoom in further?

“Hopefully, there will be more of this kind of technology moving forward, so if we can sort of be the tip of the spear and get some information to share with other people, we’d like to be able to do that.”

The map is available for viewing on the Alberta Parks website at https://albertaparks.ca/albertaparksca/advisories-public-safety/outdoor-safety/winter-safety/ates-disclaimer/kananaskis-country-avalanche-terrain-ratings-scale-ates.

A screenshot of the area covered by the Automated Avalanche Terrain Exposure Scale (AutoATES) map in Kananaskis Country. Colour coded areas range from red, demonstrating extreme avalanche terrain hazard to no defined colour, meaning there is no avalanche risk. Alberta Parks Screenshot